Tutorial 2.a: Representing and Evaluating Uncertainty for Classification¶

The structure of this tutorial will mirror that of Tutorial 1.a. Tutorial 1.a focuses on regression problems, while the current tutorial focuses on classification problems.

Before we start to work with any predictions, we must first think about how to represent our prediction. For example, when predicting image classes, we can represent the prediction as a categorical distribution over all possible labels, or as a set of likely labels. Each representation has its pros and cons. Depending on the different requirements during training/deployment, we may even want to convert between different representations.

This notebook aims to introduce some popular representations, as well as metrics to measure the quality of the predictions.

We first list the types of predictions currently supported by torchuq for classification. You can skip this part and come back later as a reference.

Name |

Variable type/shape |

Special requirement |

torchuq sub-modu le for evaluati on |

|---|---|---|---|

Topk |

``int array [batch_siz e] or [batch_size, k]` ` |

Each

element

take values

in

|

``torchu q.evalua te.topk` ` |

Categorical |

|

Elements

should be

in

|

|

USet |

|

Elements are 0 or 1 |

``torchu q.evalua te.uset` ` |

Ensemble |

|

name must start with prediction type and a string (with no special characters) , such as ‘categorica l_1’ |

Unavaila ble |

# We must first import the dependencies, and make sure that the torchuq package is in PYTHONPATH

# If you are running this notebook in the original directory as in the repo, then the following statement should work

import sys

sys.path.append('../..') # Include the directory that contains the torchuq package

import torch

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

As a running example, we will use existing predictions for CIFAR-10. We first load these predictions.

reader = torch.load('pretrained/resnet18-cifar10.pt')

# These functions transform categorical predictions into different types of predictions

# We will discuss transformations later, but for now we will simply use it to generate our example predictions

from torchuq.transform.direct import *

predictions_categorical = reader['categorical']

predictions_uset = categorical_to_uset(reader['categorical'])

predictions_top1 = categorical_to_topk(reader['categorical'], 1)

predictions_top3 = categorical_to_topk(reader['categorical'], 3)

labels = reader['labels']

1. Top-k Prediction¶

The simplest type of prediction specifies the top-k labels (i.e. the k

most likely predicted labels). The labels are represented as integers

. A batch of

top-k prediction is represented by an integer array of shape

. A batch of

top-k prediction is represented by an integer array of shape

[batch_size, k], where predictions[i, :] is a sequence of labels

(which are represented as integers). A top-1 prediction can be either

represented as an array of shape [batch_size, 1] or more

conveniently as an array of shape [batch_size].

Here, we first verify that the loaded top3 and top1 predictions have the correct shape.

print(predictions_top1.shape)

print(predictions_top3.shape)

torch.Size([10000])

torch.Size([10000, 3])

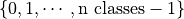

A very natural way to visualize the quality of a top-1 prediction is by

the confusion matrix: among the samples that are predicted as class

, how many of them actually belong to class

, how many of them actually belong to class  . To plot

a confusion matrix in torchuq use

. To plot

a confusion matrix in torchuq use

torchuq.evaluate.topk.plot_confusion_matrix.

from torchuq.evaluate import topk

topk.plot_confusion_matrix(predictions_top1, labels);

We can also evaluate metrics for these predictions, such as accuracy

print(topk.compute_accuracy(predictions_top1, labels))

print(topk.compute_accuracy(predictions_top3, labels))

tensor(0.9524)

tensor(0.9951)

2. Categorical Prediction¶

The categorical prediction is perhaps the most useful prediction type

for classification. This type of prediction returns the probability that

a label is correct for each possible label. In torchuq a categorical

prediction is represented as a float array of shape

[batch_size, n_classes], where predictions[i, j] is the

probability that the  -th sample takes the

-th sample takes the  -th label.

-th label.

print(predictions_categorical.shape)

torch.Size([10000, 10])

Confidence Calibration. Given a categorical prediction

![p \in [0, 1]^{\text{n classes}}](../../_images/math/5fa66c3850b83f0a4ab2471875b069802cbe4a5b.png) , the confidence of the

prediction is the largest probability in the array:

, the confidence of the

prediction is the largest probability in the array:  .

If this largest probability is close to 1, then the prediction is highly

confident. A simple but important requirement for this type of

prediction is confidence calibration: among the samples with confidence

.

If this largest probability is close to 1, then the prediction is highly

confident. A simple but important requirement for this type of

prediction is confidence calibration: among the samples with confidence

, the top-1 accuracy should also be

, the top-1 accuracy should also be  . For instance, if

a model is 90% confident in each of 100 predictions, it should predict

the correct label for 90 of the samples. If this property doesn’t hold,

then these confidence estimates are not meaningful.

. For instance, if

a model is 90% confident in each of 100 predictions, it should predict

the correct label for 90 of the samples. If this property doesn’t hold,

then these confidence estimates are not meaningful.

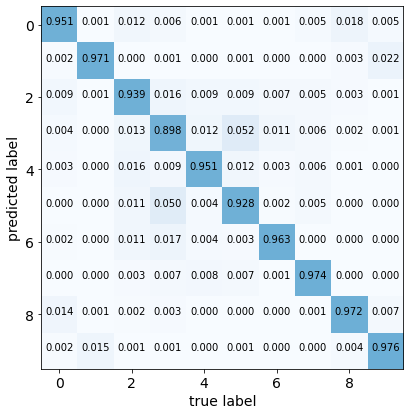

We can visualize confidence calibration by plotting the reliability

diagram, which plots the (actual) accuracy  among samples with

predicted confidence

among samples with

predicted confidence  vs. the predicted confidence

vs. the predicted confidence  .

Ideally the predicted confidence

.

Ideally the predicted confidence  will be equal to the actual

accuracy

will be equal to the actual

accuracy  , so a perfectly calibrated model will yield a

diagonal

, so a perfectly calibrated model will yield a

diagonal  line. Deviations from this line represent

miscalibration. As an example, we plot the reliability diagram for our

example predictions below, and it is clear that the predictions are not

well-calibrated. For example, among all samples with a confidence of

about 0.9, the accuracy is only about 0.8. Hence the accuracy is lower

than the confidence, and the predictions are over-confident.

line. Deviations from this line represent

miscalibration. As an example, we plot the reliability diagram for our

example predictions below, and it is clear that the predictions are not

well-calibrated. For example, among all samples with a confidence of

about 0.9, the accuracy is only about 0.8. Hence the accuracy is lower

than the confidence, and the predictions are over-confident.

We can also compute the expected calibration error (ECE), which is a

single number that measures mis-calibration. The ECE measures the

average deviation from the ideal  line. In practice, the ECE

is approximated by binning — partitioning the predicted confidences into

bins, and then taking a weighted average of the difference between the

accuracy and average confidence for each bin. Pictorially, it is the

average distance between the blue bars and the diagonal in the

reliability diagram below.

line. In practice, the ECE

is approximated by binning — partitioning the predicted confidences into

bins, and then taking a weighted average of the difference between the

accuracy and average confidence for each bin. Pictorially, it is the

average distance between the blue bars and the diagonal in the

reliability diagram below.

from torchuq.evaluate import categorical

categorical.plot_reliability_diagram(predictions_categorical, labels, binning='uniform');

print('ECE-error is %.4f' % categorical.compute_ece(predictions_categorical, labels, num_bins=15))

ECE-error is 0.0277

3. Uncertainty Set Prediction¶

The next type of representation is (uncertainty) set predictions.

Uncertainty sets are almost the same as top-k; the main difference is

that for top-k predictions, k must be specificed a priori, while for

uncertainty sets, k can be different for each sample. In torchuq,

uncertainty set predictions are represented by an integer array of shape

[batch_size, n_classes], where predictions[i, j] = 1 indicates

that the  -th sample includes the

-th sample includes the  -th label in its

uncertainty set, and

-th label in its

uncertainty set, and predictions[i, j] = 0 indicates that it is not.

For set predictions, there are two important properties to consider:

The coverage: the frequency with which the true label belongs to the predicted set. A high coverage means that the true label almost always belong to the predicted set.

The set size: the number of elements in the prediction set

Ideally, we would like high coverage with a small set size. We compute the coverage and the set size of the example predictions below.

from torchuq.evaluate import uset

coverage = uset.compute_coverage(predictions_uset, labels)

size = uset.compute_size(predictions_uset)

print("The coverage is %.3f, average set size is %.3f" % (coverage, size))

The coverage is 0.987, average set size is 1.268

![[0,

1]](../../_images/math/6b9f81517d068b15662f9d548d2c450bfe192115.png) and sum to

and sum to